I was going back through some of my blog posts the other day, when I suddenly realised something that I can only describe as appalling.

It seems everything I've done do far has been a bit, well, contemporary. Today, I'm going to put that right, by taking a look at the megafaunal extinctions that took place in the late Pleistocene.

Starting with the general factoids, 50000 years ago, there were >150 species of megafauna. However, by 10000 years ago, at least 97 were gone

(Barnosky et al., 2004). Species lost include the

Diprotodon and the

Mastadon.

|

| R.I.P. : The diprotodon, otherwise know as 'the giant wombat'. |

There are a number of theories for what caused the extinctions, it seems highly probably that each continent experienced extinctions at different times, driven by different... drivers.

Specific theories include: Climate change, overkill, blitzkrieg (rapid overkill), changes in the nutrient cycling

(Faith, 2011).

But where does this fit into the context of invasive species?

Well,

Barnosky et al (2004) speculate that the magnitude of extinctions in Africa and Central Europe where milder than elsewhere as humans co-evolved with megafauna there for hundreds of thousands of years. On the other hand,

humans were an invasive species in the Americas and Australia.

Now this is interesting. Throughout this blog I've covered several examples of human facilitated invasions, but humans as an invasive species themselves seems like a very intriguing concept indeed...

The theory of humans as invasive species would explain the magnitude of extinctions in the Americas and Australia. The main extinction pulse in Australia came after human arrival and does not seem to match and many regional or global climatic changes

(Barnosky et al., 2004).

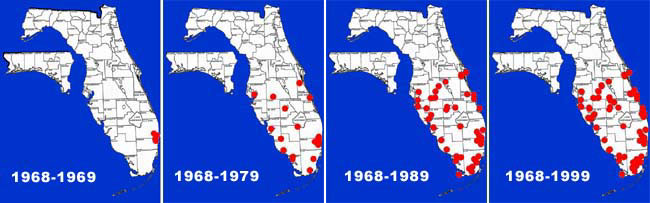

|

| Summary of megafauna extinctions on each continent. Source: Barnosky et al., 2004. |

On the other hand, the theory fails to offer insight as to why any extinctions took place in Africa or why Europe lost 36% of megafauna

(Barnosky et al., 2004).

And additionally, the Australian extinction chronology is highly uncertain. Analyses indicate that of 21 extinct megafauna genera, 12 persisted to at least 80000 years ago, and at least 6 persisted to 51-40000 years before present. The arrival of humans can only be said to have been in the range of 71.5-44.2 thousand years ago. Pretty large range there...

There are also situations where it seems climate change is a far bigger player in extinctions than any humans as invasive species cause.

For example, at least 24 large mammals are known to have disappeared from Africa during the Late Pleistocene. However, there is little reason to believe that humans played an important role in African megafaunal extinctions

(Faith, 2014).

And briefly going back to Australia, new evidence throws human impact into doubt even there, with suggestions that climate changes, not anthropogenic burning, was responsible for changing conifer dynamics, which would have had a knock on effect on megafauna

(Sakaguchi et al., 2013). Though at the same time, the authors do not rule out a hunting effect...

|

| Not a burning issue in this case? |

To conclude, the issue of humans as invasive species in the decline of megafauna seems to be incredibly complex. Indeed the relative importance of climate change and impacts of newly arrived human populations remains highly controversial (

Prescott et al., 2012).

But hey, I'm sure that as our knowledge and dating techniques improve, the picture will become clearer.

Hope you enjoyed the journey back in time, next time we'll be back in the present day where I'll be wrapping the blog up

:'-(

Over and out

The Invader Inspector